February 10th 1942 – James Dillon criticises Irish neutrality at Fine Gael ard fheis

The TD for Monaghan resigned from the party shortly after.

On February 10th 1942, Fine Gael held its annual conference, or ard fheis, in the Mansion House in Dublin. It was a relatively low-key affair, with only a couple of hundred delegates in attendance, taking place as it did during the state of “national emergency” which the Irish government had declared at the start of the Second World War. The official stance of the Irish state during the war was one of neutrality: the Taoiseach and leader of Fianna Fáil, Éamon de Valera, spoke in Dáil Éireann on September 2nd 1939 – the day after Germany invaded Poland – telling those assembled that it was “the aim of Government policy, in case of a European war, to keep this country, if at all possible, out of it”, while acknowledging that “when you have powerful states in a war of this sort, each trying to utilise whatever advantage it can for itself, the neutral state, if it is a small state, is always open to considerable pressure.”

Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael had butted heads on several issues over the previous decade, but on the subject of Irish neutrality, both de Valera and W. T. Cosgrave, the leader of Fine Gael, were in agreement. In a debate on July 17th 1941, Cosgrave said, “the best contribution we, as public men, could make in this difficult situation in which we find ourselves is to show that there is a united front as regards the policy of the country in connection with the war; that we are united in the view that neutrality is the best policy for the country at the moment.” Cosgrave had issued a statement ten days prior to the 1942 ard fheis, urging “public men to preserve a discreet silence on external affairs”, a reference to the ongoing war. However, not all in Fine Gael shared this view. James Dillon, TD for Monaghan, had confided to his brother Myles in September 1939 that he believed “our neutrality is a disastrous mistake.”

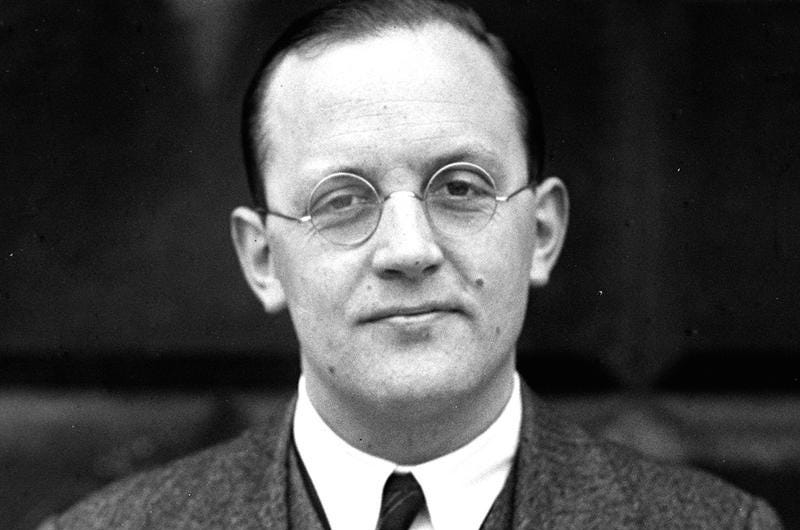

Dillon was the son of the late John Dillon, the MP for East Mayo who succeeded John Redmond as leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party, standing down after the disastrous election of 1918, in which the party went from 68 Westminster seats to a mere six. Before following his father into politics, Dillon was called to the bar in 1931. He was elected TD for Donegal in 1932, first as an independent, then as co-leader of the National Centre Party, which merged with Cumann na nGaedheal in September 1933 to form Fine Gael. In 1937, Dillon was elected as TD for Monaghan, a position he would hold until 1969, when he retired from politics.

Though Dillon had made it clear in Dáil debates that he did not believe Irish troops should be sent abroad (“We have neither the means nor the material with which to equip such forces”) he said that “we should ascertain precisely what co-operation Great Britain and the United States of America may require to ensure success against the Nazi attempt at world conquest”. Dillon also drew parallels between Ireland’s history, and the various European countries – such as Yugoslavia, Holland, Norway, Belgium and Denmark – which had been invaded by Germany: “I say to-day that the German Nazi Axis seeks to enforce on every small nation in Europe the same beastly tyranny that we successfully fought 700 years to prevent the British Empire imposing on this country.”

The 1942 Fine Gael ard fheis was held a little over two months after the United States officially entered the Second World War, when Pearl Harbour was attacked by Japanese forces. This event had had a profound effect on Dillon, though the official party line of Fine Gael was to maintain neutrality. Cosgrave told those in attendance at the Mansion House, “I am not aware of any remarkable change in the war situation which would justify alarming pronouncements. Already many of our people have felt the privation arising out of the war. Their sufferings are quite enough for them.”

Dillon’s speech before party delegates was quite different. He referenced the recent attack on Pearl Harbour, and condemned the Axis powers: “Whoever attacks America is my enemy, without reservation or qualification, and I say that the United States has been treacherously and feloniously attacked by Germany, Italy and Japan.” He then went on to reference what he saw as the historic debt owed by Ireland to America for the many millions who had been taken in over the previous century: “I say to our friends throughout the country that their eyes should be open to the dangers that beset us, and, whatever and whenever they hear the suggestion made that Americans are putting us in a position of embarrassment or of difficulty, let them think with me of their fathers and mothers and sisters who found safety, refuge and welcome in America when there was nowhere else they could get them.”

Dillon’s words were met with a mixed reception. Though he was elected vice-president of Fine Gael at the conference, he was criticised by some delegates for wanting to “forego our neutrality and throw our lot in with the Allies.” The novelist Elizabeth Bowen wrote in a report to the Dominions office that “of the people there one-third were strongly with Dillon; one-third were neutral (temporarily swayed, but due to react against him later); one-third definitely hostile.” John Maffey, the British representative to Ireland, wrote to Dillon shortly afterwards, saying, “it may be undiplomatic of me to say that your courageous action strikes a very sympathetic chord in our hearts here and across oceans wide and narrow.”

Nonetheless, when Dillon met with Cosgrave and other senior members of Fine Gael – Richard Mulcahy, Patrick McGilligan and Thomas F. O'Higgins – at party headquarters after the ard fheis, it was made clear that his speech was a resigning matter. He stood down as vice president of Fine Gael less than ten days after he had been elected. Cosgrave responded by saying, “A sense of duty has compelled you to pursue a particular course in relation to external policy in the emergency of which we could not, in the interests of the country, approve.”

Dillon remained a TD for Monaghan as an independent throughout the rest of the decade, but rejoined Fine Gael in 1952, serving as Minister for Agriculture from 1954 to 1957, and then leader of the party from 1959 to in 1965. He died on February 10th 1986, exactly 44 years after the speech which led to his resignation from Fine Gael. The Taoiseach, Dr Garret FitzGerald, said that Dillon “had immense political courage and total political integrity. He did what he thought was right; it would never have occurred to him, to trim his sales to electoral winds.” W. T. Cosgrave’s son Liam Cosgrave, who had succeeded Dillon as leader of Fine Gael, said “he was reminiscent of [Daniel] O’Connell with his rich speaking voice, his wit and learning, his powerful presence and personality.” Charles Haughey, leader of Fianna Fáil, spoke fondly of Dillon also, saying, “Those of us who differed from him politically could not but admire his great ability, his wide knowledge of public affairs and his unfailing courtesy at all times and in every situation.”

Sources

Dáil Éireann debate - Thursday, 17 Jul 1941, Vo. 84 No. 14.

‘Friend of Britain in Eire: Mr Dillon Resigns from the Cosgrave Party’, The Scotsman, 20 February 1942, p. 6.

‘Irish Depend on U.S. Friendship: Dillon Warns Against Nazi Co-Operation’, Dundee Courier, 11 February 1942, p. 3.

Manning, Maurice, James Dillon: A Biography (Dublin: Wolfhound Press, 1999).

O’Day, Alan and John Stevenson (eds), Irish Historical Documents since 1800 (Dublin: Gill & Macmillan, 1992).

‘Death of a Statesman: James Dillon 1902 – 1986’, Irish Independent, February 11 1986, p. 6.